Best Ball Basics and a Cheat-sheet for Success

The new and improved way to play fantasy football

Over the last few years, I’ve often been asked, “what are all those football drafts you post on Twitter during the summer?” Best ball is, of course, the answer.

The Start

Best ball started for me back in the 2016. After a few years of cranking up the ol’ ESPN mock draft lobby each May, with the chance to win exactly $0 and the privilege to draft against a room full of autodrafters and trolls, I stumbled on to the site “Draft”. Draft had a simple premise. Draft a team of 18 NFL players and don’t do anything else. No waivers, no trades, no start-sit dilemmas, nothing. Your roster would be auto-managed and optimized throughout the season. Over the course of 2016 and 2017, I probably did hundreds of drafts on Draft, selecting Lamar Jackson, Dak Prescott, and Patrick Mahomes in the early double-digit rounds and destroying a bunch of 12-man cash leagues. Needless to say, I was hooked.

Unfortunately, Draft was acquired by Fanduel, who inexplicably ended the company, leading to a vaccuum in the growing best ball space. Luckily, a few companies have filled that vaccuum, including industry-leader Underdog Fantasy, with many of the same people who started Draft. Now, in 2023, best ball is bigger than ever.

The Basics

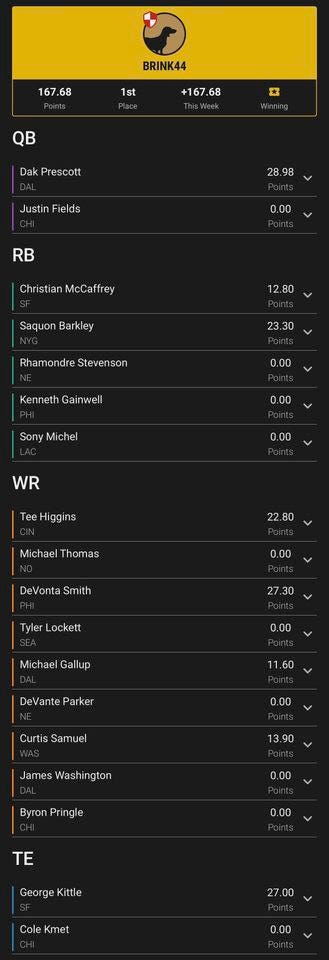

Regardless of which site you play on, the basics of best ball are the same. You’ll draft a team of 18-20 players (or 28 for the true sickos and degenerates). After the draft, there is no management of the team. No waivers, no trades, and no start-sit decisions. Each week, the computer will optimize your team’s scoring to fill your lineup. The scoring on each site is slightly different, with Underdog offering straightforward half-PPR, Drafters using simple PPR, FFPC offering PPR + TE premium, and DraftKings using it’s unique PPR + heavy bonuses format. As for the lineup, it usually consists of roughly 1 quarterback, 2 running backs, 3 wide receivers, 1 flex, and 1 tight end, but that again can slightly vary by site and contest. The rest of your team’s scoring remains on the bench and does not count towards your weekly score. See an example team that got me to the finals one of Underdog’s Puppy tournaments last year.

Back in 2016, almost all of the contests were simple 12 person leagues like you would find in your hometown fantasy league. While drafting is fun, it wasn’t a hobby that could lead to a huge financial boom. Despite drafting the elite quarterbacks of today in the 11th round, and generating a huge ~75% ROI, I was still only winning $1000 or so each year. But, with the tournament formats like the one the team above was drafted in, that landscape is much different now.

The Present and Future

Over the last few seasons, best ball has seen an exponential rise, largely driven by the folks at Underdog Fantasy. Underdog has popularized larger tournaments, where after the first 14 weeks of competing in your typical 12-person league, you go on to competing against the best teams in in the three weeks of the season. Each round is a winner advances, losers go home (with a small prize), ending in an ultimate week 17 sweat where the final teams have a chance to win life-changing money.

Their flagship product, Best Ball Mania, is the leading edge of this type of contest. It was first offered in 2020, with 43,000 entrants, $1 million in total prizes, and $200,000 to first place. Now, in 2023 with Best Ball Mania 4, it’s grown to a whopping 677,000 entrants, $15 million in total, and $3 million to first, as well as offering cash prizes to the best regular season teams as well. This growth has led to an explosion of content and analysis of the ways to attack these large tournaments, and has ended the days where we could draft Lamar Jackson and Patrick Mahomes in the 11th round. However, many of the simple tenets to best ball success remain.

Foundational Principles to Winning Life-Changing Money

I’m far from the first person to analyze how to attack best ball, with Shawn Siegele, Michael Dubner, Conor O’Driscoll, Mike Leone, Pat Kerrane, and many others creating manifesto-level research that explore the minute tactics and strategy (and in Leone’s case it’s roughly 1/2 the length of the Unabomber’s manifesto). That said, it is extremely difficult to properly weigh all of these factors when you’re drafting with 30 seconds on the clock. For true success, the words, “tacit knowledge” come to mind. However, in the absence of an AI capable of synthesizing all of that into decision-making process, we must create a mental model that does the best we can. Below is my simple method (or heuristic for you fellow nerds out there) that I draft off of.

1. Positional Scarcity (Which position is replaceable later?)

While it is true that running backs often score more points than wide receivers, quarterbacks score the most out of anyone, and tight ends score the least of all positions, none of that occurs in a vaccuum. While Josh Allen may score the most points of any player at 450, if Jared Goff scores 375 points and is drafted 10 rounds later at QB15, Josh Allen’s value takes a hit, as quarterback production is more easily replaced later in the draft than other positions.

Similarly (as is the case on Underdog right now), if I have to start 3 wide receivers but only 2 running backs, then even if the RBs score more, the value of wide receivers goes up. Historically, the market has undervalued this, leading to inflated running back ADPs and an easy edge for savvy drafters to exploit. However, at least on Underdog, the market has finally started to wisen up. How to attack that changing market will be one of the critical questions to answer for success this season (more on that in my upcoming articles). But generally, the first question I ask myself before each pick, is “what position can I draft later that offers similar value and/or upside to a player available?” Hint: It’s almost never a wide receiver.

2. Roster construction (Which position maximizes my current team the best?)

While tacit knowledge is a key part of current roster construction, there are some general guidelines (not actual rules) we can follow, backed by data over the last decade. The challenge, as Sam Hoppen details here, is that this data is predictive and not descriptive, and we must adapt it for the evolving landacape. With that said, there are a few basic running back constructions (definitions can vary) I usually draft.

Zero RB: No RB before round 6, draft 6/7 RBs total.

Anchor RB: 1 RB in first three rounds, draft 5/6 total.

Double-Anchor RB: 2 RBs in the first three rounds (maybe four in today’s market), draft 4 /5 total.

Hyperfragile: 3 RBs in the first five rounds (maybe six in today’s market), draft 4 total.

The other positions are usually derived from my running back strategy.

At QB/TE, 2 or 3 total at each position. If I draft a QB or TE before round 7, then I’m only drafting 2 total at the position. If after round 7, I’m usually drafting 3 total.

Wide receiver is almost exclusively derived from the above constructions, but my general rule is I was good ones early, and at least 1 WR for each two picks I make in the first ten rounds.

Ensuring you have a good roster construction simply allows you to maximize the efficiency of your team. With it, you’ll waste less quality scores at a position and instead score those points at the position that you need it. Rotoviz has been and remains the king of roster construction, so I’d recommend exploring the Rotoviz Roster Construction Explorer. It is one of the best tools out there.

3. Value (Who can I draft after ADP?)

In the old school 12-person contests of 2016, ADP was mostly just a construct forced upon us. While it is directionally correct, there were certain players and archetypes that the market undervalued where I was comfortable reaching a round to two ahead of ADP to select. As mentioned before, that led me to Lamar, Dak, and Mahomes, each of whom I had on more than 50% of my teams back in 2016-2017. However, that logic significantly changes in these big tournaments.

While identifying these players and archetypes still matters (see #5 below), ADP value matters more. To win a 677,000 field tournament, I not only need to identify players and archetypes the market is undervaluing, I need to draft those players at a similar or cheaper cost than my (skilled) opponents. While some opponents may lack the skill or awareness to properly construct (#2) or correlate (#4), leading them to waste these talented players, the skilled opponents we will likely face for the top prizes will be utilizing these strategies. The cost we paid will be one of the best and only ways to beat well-crafted teams.

4. Correlation (Who is available that is correlated to players already on my team?)

Every pick we make assumes something. If I draft Ja’marr Chase, I am assuming Burrow is healthy and playing relatively well. Without Burrow, Chase is very unlikely to be a part of an elite team. So, after drafting Chase, I should value Burrow higher relative to the rest of the drafters in my room, potentially even selecting him before ADP. However, as we seen from the Value section above, the more people we are competing against, the less we should be willing to do this. Ideally, we want to both stack Burrow on our Chase teams AND do it after ADP. That is obviously difficult to do, as almost everyone wants to draft a player like Burrow. However, we shouldn’t be afraid of other drafters sniping our potential stack quarterbacks, especially early, as we have more options for stacks at quarterback throughout the draft.

That said, we do need to be a bit more aggressive after we have a quarterback. If we spent an early pick on Patrick Mahomes, but we don’t have Travis Kelce (for shame), then there a plethora of medicore Chiefs WRs for us to target. While again it is optimal for us to draft those players at a value, ADP value matters less the later in the draft we go. With a more passing-centric QB like Mahomes (if he succeeds, it’s likely one of his pass-catchers is too), ensuring we get the stack by reaching a round or so ahead of ADP is probably worth the slight loss of value.

As with all things best ball, tacit knowledge rules, but the below should again serve as a guideline.

Best: Stacked at ADP value

Good: ADP value but unstacked (but you have other stacks)

Good: Stacked at ADP

Good: Stacked ahead of ADP in later rounds (10+)

Fine: Stacked ahead of ADP in early rounds (9 or earlier)

Bad: Unstacked and ahead of ADP (generally this is a sign you love a specific player too much and are ignoring his downside risk. Examples were Elijah Moore and Kyle Pitts for me last year.)

Ultimately, our goal with correlation is to use bridging assumptions to increase our upside and reduce the number of things we get right. More to come on this in the specific tournament articles, but for now, just don’t forget about week 17 (it’s either all that matters or 2/3 of what matters).

5. Specific Players and Archetypes (Which players can generate more value and upside than their ADP suggests?)

Over the years, there’s been tons of micro edges with specific players and archetypes. Rookies often break out late in the season, generating upside exactly when we need it most. Second-year wide receivers often beat and smash their ADPs, offering an archetype that we should almost blindly fire at. Rushing quarterbacks offer a higher floor and ceiling than pocket passers. Player X is very good at football, and I don’t think the market is evaluating him correctly. The list goes on and on. For the casual NFL fan, this is often the most fun, as we love predicting who is good and who is bad. It’s the simplest and purest form of enjoying sports.

However, it is also the most volatile of all our edges. Sometimes we can identify a very talented player, who was great as a rookie and is set for a second-year breakout, and that player runs into the worst offensive environment since the invention of the forward pass and is a horrible bust (Kyle Pitts). Sometimes a similarly talented player runs into the combination of Zach Wilson as his quarterback and a more talented wide receiver coming to the picture (Elijah Moore). My point here is that it is perfectly fine to predict who will be good. If you’re right, that can be a huge edge. But be careful, as you can be right about the player, and it can still go horribly wrong. Follow the first 4 guidelines of the heuristic first before firing away at the player for yet another draft.

For the purposes of the 2023 landscape, the market is much wiser to many of the edges listed above. I will inevitably have players I value higher than the market. Kyle Pitts (at his much reduced ADP from last year) again remains one of them. Chuba Hubbard, a player I’ve never drafted much of in previous year, is another, as he is just so cheap relative to my opinion of him and his situation. I will likely be overweight both of these guys. You will have similar stands. Just be sure you are drafting them in a way that maximizes the specific team you are building at that time.

Recap and Cheatsheet:

To recap, best ball is, in my opinion, that best way to play fantasy football today, as we get to draft teams and root for them without any tedious weekly work. It has grown massively the last few years, and there’s no end in sight. Playing and winning in this environment is more challenging than a few years ago, but we still have many levers we can pull to help us succeed. The key five principles are as follows:

1. Positional Scarcity (What is replaceable later?)

2. Roster construction (What position maximizes my current team the best?)

3. Value (Who can I draft after ADP?)

4. Correlation (Who is available that is correlated to players already on my team?)

5. Specific Players and Archetypes (Which players can generate more value and upside than their ADP suggests?)

Happy drafting, and please reach out with any questions or comments you have in the comment section or on my Twitter. Cheers!